For the tourists wandering the boardwalks along the travertine terraces of Mammoth Hot Springs, Tuesday was just another crisp, clear autumn afternoon in Yellowstone National Park. But inside an employee gymnasium a few hundred yards away, some of the sharpest scientific minds in the region were sharing the results of cutting-edge research with colleagues, land managers and others.

The 12th Biennial Scientific Conference on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is being held over three days this week at Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel, centered on a theme of “Crossing Boundaries.”

But judging from some of the comments during Tuesday’s panel discussions and coffee breaks, it seemed like the conference itself had at times crossed a boundary from the world of esoteric hypotheses posed by cautious researchers into a realm of eager discovery and engaged debate by journalists, advocates and members of the general public.

“For me, this is super-exciting to see, and the mere fact that the public is this interested is a good thing,” said David Hallac, the park’s lead scientist and division chief of the Yellowstone Center for Resources.

“It’s a rare chance for people to get the latest information directly from the scientists doing the research,” said Hallac, a conference organizer who oversees science and research on the park’s wildlife, habitat and cultural resources.

Dozens of biologists, graduate students and other researchers from state and federal agencies offered an intense series of brief but dense presentations on projects examining issues that transcend the boundaries of Yellowstone, ranging from fire and disease to migrations and climate.

Only a single reporter sat through all of the 2012 conference. But Hallac said about a dozen members of the news media had registered for this year’s conference, which remains heavy on PowerPoint presentations full of charts and graphs, maps, bell curves, data tables and the occasional quadratic equation.

Some of Tuesday’s most popular presentations differed from previous years by including compelling storytelling, emotionally engaging photography and other emotionally powerful elements that help connect raw data to critical policy issues that affect wildlife, people and the regional landscape.

“We didn’t see a lot of this two years ago, and I think we have to recognize that the way we used to communicate a lot of this information is changing,” Hallac said.

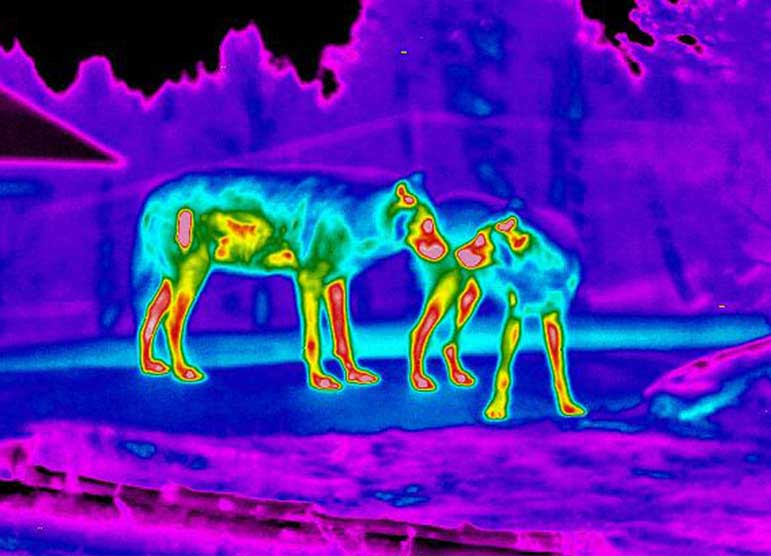

Advances in technology also played a role in many of the studies discussed Tuesday, as researchers offered up detailed data about long-distance elk and mule deer migrations that relied on sophisticated, remote-controlled cameras and advanced GPS collars. Others shared findings from separate studies that used thermal imaging cameras and high-resolution photos submitted by park visitors to study sarcoptic mange among gray wolves.

Absent from many of the discussions, though, was the perspective of private landowners, a deficiency that amounted to a “glaring gap” in the program, said Charles Preston, curator of the Draper Museum of Natural History at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyo.

Large, private tracts bordering wilderness and other public lands play a key role in the regional conservation picture, Preston said, and the voices of those landowners should be a part of discussions about key management issues.

“Wildlife does not respect political boundaries” Yellowstone Superintendent Dan Wenk said. “So we have to realize that when it comes to a wide range of conservation issues, Yellowstone National Park can’t do it alone. We have to continue to engage with the states and surrounding communities.”

Wenk said that most people support a wide range of shared common goals aimed at protecting wildlife and key habitat, but even when science offers clear guidance on management options, finding a politically practical solution can prove problematic.

That’s why it won’t be just elk and bison being studied by Yellowstone scientists in the months to come, but park visitors and the general public as well, Wenk said. The superintendent will be seeking more data from social scientists about public opinion on a wide range of issues as he seeks to find consensus on sensitive matters like bison management and native fish restoration.

Hallac said a newly hired social scientist will be joining the ranks of Yellowstone’s researchers, with the goal of gathering more detailed public opinion and cultural background on topics ranging from trout fishing to first impressions from new park visitors.

“In a lot of ways, we’ve done all this amazingly detailed research on, for instance, wolf ecology, and we know so much about it,” Hallac said. “But we’re realizing we still need to learn more about how people think and feel about this place.”

Contact Ruffin Prevost at 307-213-9818 or [email protected].