CODY, WYO. — Grizzly bears, gray wolves and bison top the list of animals that literally stop traffic across Yellowstone National Park all summer long. But if one Wyoming researcher had his way, park visitors would be snapping a lot more photos of fringe-tailed bats and golden-mantled ground squirrels.

While it’s the charismatic megafauna that capture public attention and research dollars, the less heralded mammals of Yellowstone and Wyoming are just as important. But not nearly enough is known about these smaller species, said Steven Buskirk, a professor emeritus of zoology and physiology at the University of Wyoming.

“We know some species of mammals a lot better than others,” Buskirk said during a lecture last week at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. About 25 percent of the park and state’s mammals account for more than 75 percent of published scholarly research on the entire range of mammals found in Wyoming, he said.

“We know some species of mammals a lot better than others,” Buskirk said during a lecture last week at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. About 25 percent of the park and state’s mammals account for more than 75 percent of published scholarly research on the entire range of mammals found in Wyoming, he said.

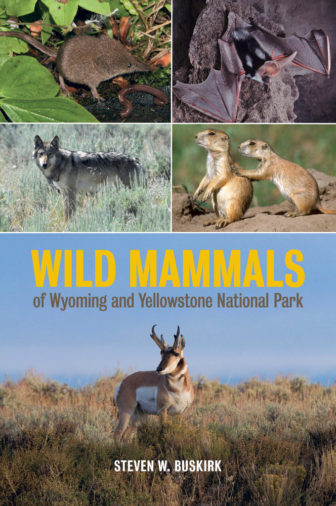

Buskirk is the author of the newly released “Wild Mammals of Wyoming and Yellowstone National Park,” which covers 117 mammal species known to inhabit the park and Wyoming. Yellowstone is home to 67 mammal species, the largest concentration in the 48 conterminous sates.

A major goal in compiling the book was to “provide uniform coverage across species,” Buskirk said, paying just as much attention to the Preble’s shrew as mule deer or elk.

Thousands of popular publications, journal articles and books cover elk in every conceivable detail, Buskirk said.

“But if we want to write about the Preble’s shrew, there are only a couple of paragraphs in only a couple of publications,” he said.

Part of the problem lies in the difficulty in finding, observing and capturing elusive animals like shrews. But other mammals, like rabbits or squirrels, appear so common and everyday that the public and academia tend to take them for granted, often confusing one species of small mammal for another.

Researchers can’t expect state and federal agencies to spend limited resources learning about “unpopular” but “common” mammals.

“Instead, we need to do what the bird people do. We need to be able to use citizens and their observations to figure out what animals are where and in what abundances,” he said.

While birds are welcomed in most backyards across the country, small mammals are considered invaders to be eradicated, even though many homeowners can’t tell the difference between a marmot, marten, beaver or ermine.

Schools, museums and conservation groups should develop mammal identification charts, cards, books and other resources, similar to the birding community, Buskirk said.

Learning more about bats, voles, prairie dogs and the wide range of smaller mammals is important, because they can all be vulnerable to changes that challenge their foothold on the landscape. That’s a lesson learned from the black-footed ferret, which almost became extinct, but was found in Meeteetse, Wyo. and has been slowly recovering under a heavily managed breeding program, Buskirk said.

“Our interest in these species is a reflection of human curiosity,” Buskirk said.

“In Wyoming, we’re blessed with a great diversity of native habitats that are pretty much unchanged from their pre-European condition. A lot of Wyoming is still looking like it did 150 years ago,” he said.

“But when it comes down to individual species, we still don’t know too much about a lot of these small-bodied mammals,” Buskirk said. “We can do better.”

Contact Ruffin Prevost at 307-213-9818 or [email protected].