MADISON JUNCTION, Wyo. — Over the past 151 years, people have traveled from around the world to experience the unique landscape of Yellowstone National Park because it has remained largely untouched, showing what life there has been like for thousands of years.

But for three days this week, a historic presence was briefly restored in Yellowstone after being absent for a century and a half. A village of 20 teepee lodges rejoined its rightful place among the park’s grizzly bears and bald eagles, the cottonwood trees and meandering streams, the gurgling geysers and bubbling mudpots.

“These are my homelands, among many other people who’ve come through here and called this landscape home,” said Ren Freeman during the Thursday opening of “Yellowstone Revealed,” a temporary, interactive art installation created by an inter-tribal group of Indigenous artists and scholars.

“I welcome you,” said Freeman, an Eastern Shoshone anthropologist and director of the Indigenous Research Center for Salish Kootenai College on the Flathead Indian Reservation.

“My people, as Shoshone people, we believe this land created us,” Freeman said. “I belong here. I belong to this land.”

Freeman’s deep and personal connection to Yellowstone echoed the comments of many other Native speakers at Thursday’s event. They detailed their efforts to recognize a historic presence in the park and to reconnect with the landscape while engaging with visitors by telling their stories and sharing their cultures.

The National Park Service recognizes 27 tribes as having historic and current ties to Yellowstone. Now in its second year, “Yellowstone Revealed” is one of a series of Native cultural events and installations around the park that began last year as part of the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of Yellowstone’s founding as the world’s first national park.

“Yellowstone Revealed” was created in cooperation with Mountain Time Arts, a nonprofit organization based in Bozeman, Montana that produces public art projects and programs that explore the history, culture and environment of the West and Native people.

The project, which was on view from Thursday to Saturday, allowed park visitors to explore the historic, current and future relationships between Native Americans and Yellowstone.

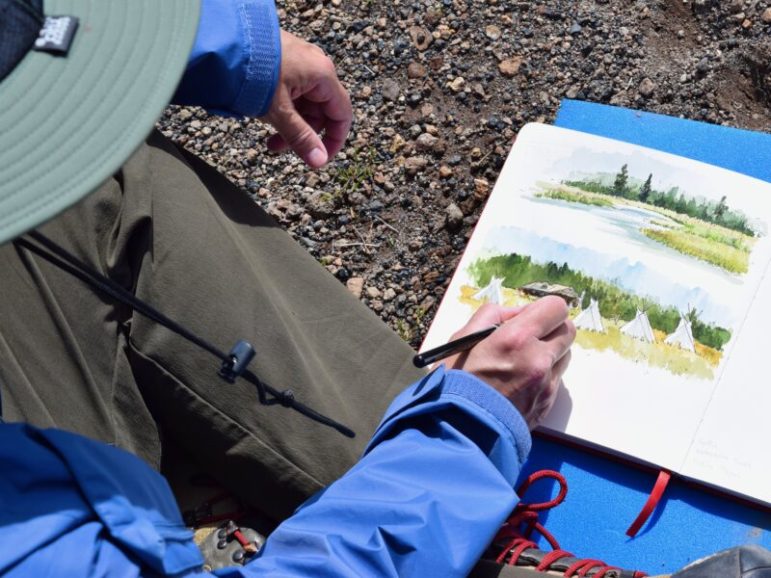

Situated in a meadow at Madison Junction where the Gibbon River joins the Firehole River to form the Madison River, the teepees combine art and storytelling at a place where Native dwellings once stood, before their owners were excluded from the park.

Symbolism behind teepees

Michael Spears, an actor, singer and Kul Wičaša Lakota from the Lower Brulé Sioux Tribe of South Dakota, spoke about some of the symbolism behind the teepees.

A traditional grandfather lodge or medicine lodge would have 28 poles, he said, which is the same as the number of ribs in a female buffalo.

“A teepee is a representation of our life,” he said. “If you look at a person’s teepee or their dwelling, you can see into their soul and how they operate, where they come from and how things are in their life.”

“It’s a circle, just like how there’s no beginning or end to our life,” said Spears, who was featured in the film “Dances with Wolves” and has appeared in several TV shows, including “Reservation Dogs” and “Longmire.”

Sean Chandler, an Aaniinen (Gros Ventre Nation) artist, created a series of 11 teepees that contrasted what Native life was like before and after contact with white European-Americans.

“When Indian people were first met by Europeans, there was always this desire to define us as low, savage, less than a human being,” said Chandler, who described his work as sometimes being “sarcastic or a little dark.”

“That same concept was drilled into our heads to be ‘nobody,’ and we could only go so far in society, and that would be it,” he said. “So that’s the kind of story that my work takes into account.”

But by also highlighting positive aspects of traditional Native culture with his teepees, Chandler said he seeks to “build and mesh these two worldviews together.”

Ben Pease, an artist with roots in the Apsaalooke and Northern Cheyenne tribes, painted one teepee yellow and decorated it with images of Indigenous men; he made a similar women’s teepee and painted it blue. The teepees play on a trick of human vision, based on how visitors’ eyes interact with the teepee colors, the sky and bright sunlight. Upon exiting the women’s teepee, a visitor’s vision is filled with a pink hue, while the men’s teepee reveals a blue color. Pease also painted a new original work during Thursday’s opening.

Susan Barnett, curator of the Whitney Gallery of Western art at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, described Pease as an important artist, and said the museum recently acquired one of his paintings because it manages to convey both traditional Native imagery and contemporary abstraction—themes also on display throughout “Yellowstone Revealed.”

Recognizing stories

“I think that if we recognize each other’s stories, it’s powerful, because we as humans share stories, and that’s where we place our values,” Pease said.

“With this installation, I think we’re here to recognize those stories that have been told on this land for millennia,” he said, referencing the documented presence of Indigenous people in Yellowstone dating back over 11,000 years.

“And we can’t forget that those lives that have been played out and lived here on this land were human lives,” he said. “The stories that everyone here has shared today are important—as important as they were thousands of years ago, hundreds of years ago—and as important as they will be into the future.”

Among the more than 100 people who attended the installation’s opening was Paul Chalfant, who drove with his wife, Diane, from Livingston, Montana to experience “Yellowstone Revealed.”

Chalfant said the millennia-long Native presence in Yellowstone has traditionally not been part of most historical accounts of the park, or was referenced only in passing.

“So just having something this big and this visible is wonderful,” he said, calling the teepee grouping “even more amazing than last year.”

“Anything the park can do to invite them back or have them back is great,” he said.

James Holt, a member of the Nez Perce Tribe who lives in Idaho, brought his son, Leo, and daughter, Sistina, to experience the “Yellowstone Revealed” opening, traveling from West Yellowstone, Montana, where he has been working this summer.

“Our own historic homeland that we would come to annually was up in the Pelican Valley here in the park,” Holt said. “So we have a history tied here that’s thousands of years old, even though we’re known as an Idaho tribe now.”

Holt said that as tribes “strengthen these relationships with the Park Service and others,” it is “very important for us to maintain a presence here.”

Those growing relationships between tribes and the Park Service got a major boost last year after “substantial outreach” that came as part of Yellowstone’s 150th anniversary, said Linda Veress, a park spokeswoman.

Veress said the anniversary was “a pivotal opportunity to listen to and work more closely with the 27 associated tribal nations connected to Yellowstone to better honor their significantly important cultures and heritage in this area.”

Many of the Native speakers and attendees at “Yellowstone Revealed” said they were eager to see it return next year and beyond, along with other similar projects in Yellowstone.

“We are not just restoring our presence from the history that some of you may know,” Freeman said. “We were removed. But we never left. So ‘Yellowstone Revealed’ is the concept of sharing with you our continuous presence.”

“It has become our way of sharing with you who we are from our perspective,” she said. “And in partnership, we are all educators.”

Republished with permission from Wyoming Truth.