By Ruffin Prevost

Yellowstone geysers have captured the imagination of visitors for centuries. But Yellowstone National Park geologists and other researchers are using an array of high-tech tools and techniques for the first time to get a much more revealing look at the park’s large-scale hydrothermal systems in action.

By combining advanced tools like infrared photography, laser image mapping and GPS locators, researchers are putting together increasingly detailed and accurate pictures of the complex underground processes that shape surface features like geysers, mudpots, hot springs and fumaroles.

Visible thermal features in Yellowstone cover less than 1 percent of the park’s land area, but they are just surface indicators of a much larger web of underground systems that scientists are keen to learn more about, said Yellowstone geologist Cheryl Jaworowski.

Jaworowski discussed her research Thursday at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, where she highlighted some of the new technology being used to measure thermal features, and explained why park scientists are interested in the big picture of what goes on under Yellowstone.

“The hydrothermal area is much more than individual thermal features such as the hot springs, the steam vents, the geysers and the mudpots. I know they capture our attention, but to think about the entire system, we have to start thinking about he landscape beyond the individual features,” Jaworowski said.

“It’s this entire system I’m interested in, and thinking about and how each of these little features connect to it in this ‘hot water system,’ or hydrothermal system,” she said.

On a practical level, it’s important for Jaworowski and her colleague, Yellowstone geologist Hank Heasler, to be able to advise park planners on how to best protect the many Yellowstone geysers and the park’s thousands of other unique thermal resources — especially when new roads, trails or structures are being built.

But in a broader sense, geologists are still working to fully understand the dynamics that drive approximately 500 Yellowstone geysers and a total of more than 10,000 thermal features. Those natural wonders were the initial reason for Yellowstone’s creation, Jaworowski said, and in 2005 Congress allocated funds for more detailed scientific monitoring of them.

Much of that work has involved taking a bird’s-eye view of things, if only birds could see infrared heat, like snakes do.

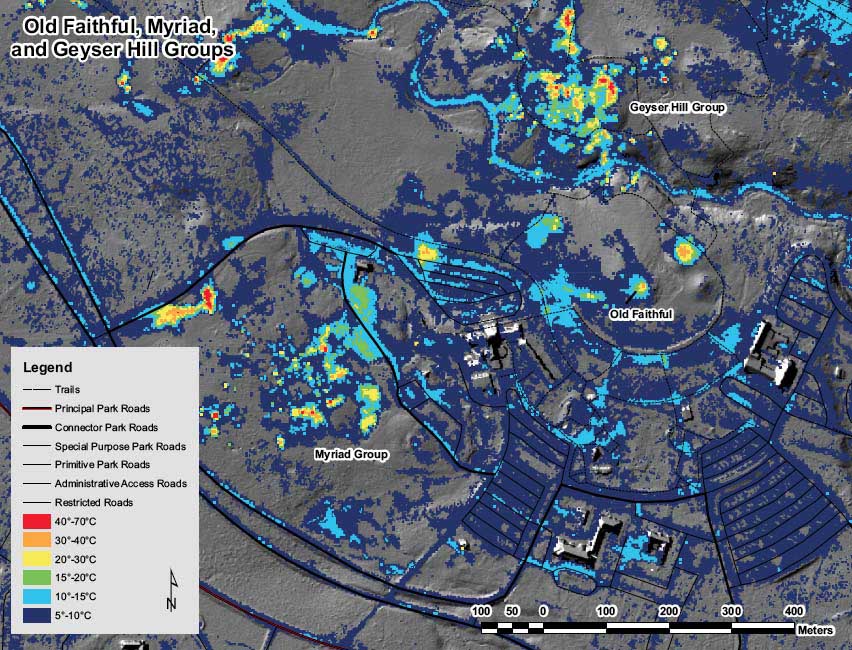

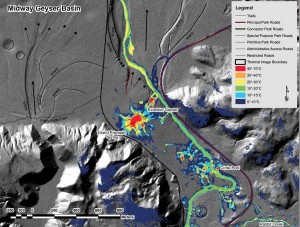

Yellowstone staff members collaborated with researchers from the Remote Sensing Services Laboratory at Utah State University on the project. Using off-the-shelf infrared cameras typically employed in home inspections to detect heat loss, researchers fly at 500 feet over the park, capturing a broad view of a specific hydrothermal system, such as Old Faithful and Geyser Hill.

They combine that image with detailed topographical mapping data captured using LIDAR, a laser rangefinder mounted on a plane that flies the same route. The images are calibrated and overlaid using known GPS coordinates and other benchmarks.

The result is an amazingly detailed composite image that is accurate to 1 meter and that shows a range of radiant temperature from about 5-70 degrees Celsius, or about 40-160 degrees Fahrenheit.

Yellowstone geysers revealed

Jaworowski had been working in Yellowstone as a geologist for a few years before she saw one of the thermal-topographic composites of an area she had mainly studied from the ground. She was amazed at how clearly she could take in a broad but detailed view of how heat moved through a complex hydrothermal system. It was a moment of epiphany, Jaworowski said.

“These pictures just set it off,” she said.

Since 2007, only a handful of Yellowstone geysers and major hydrothermal systems have been studied using the new technique, which is labor-intensive and exacting work, she said.

But researchers can also use a thermal imaging flight after a significant earthquake swarm, for instance, to quickly assess conditions in specific areas. It gives them good documentation on any changes to thermal systems, and yields some data that can be used for public safety and planning.

Geologists will also use the new tools, along with existing ground-based sensors and other traditional measurement techniques, to assess how Yellowstone’s hydrothermal systems will respond over the long term to a snowpack that was double the normal level for the 2010-11 winter, followed by this year’s relatively dry winter.

Ultimately, the data will help park geologists better understand and protect approximately 500 Yellowstone geysers and the park’s thousands of other individual thermal features, along with the much larger interconnected underground matrix that makes up the overall Yellowstone hydrothermal system.

“Yellowstone is truly unique in the world,” Jaworowski said.

“So what we’re trying to do is protect an extraordinary combination of natural processes that results in this really unique hydrothermal system,” she said.

Contact Ruffin Prevost at 307-213-9818 or [email protected].