Early tourists had to brave a roadless wilderness to see the sights of the new Yellowstone National Park. That meant supplies had to be carried by pack animals—often cantankerous mules. One such tourist was the Earl of Dunraven, an Irish noble who first visited the park in 1874. (Dunraven Pass was named after him.) Dunraven was an astute observer and a droll wit. Here’s his description of how to pack a mule.

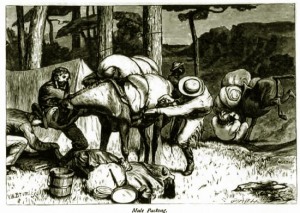

A man stands on each side of the mule to be operated upon; the saddle, a light wooden frame, is placed on his back and securely girthed. A long rope is looped into proper form and arranged on the saddle. The side packs are then lifted into position on each side of the saddle and tightly fastened. The middle bundle is placed between them—a few spare articles are flung on the top—a tent thrown over all—and the load ready to be secured.

The rope is fixed so the fall is one side and the slack is on the other. Each man places one foot against the animal’s ribs. Throwing the whole weight of his body into the effort, each man hauls with all his strength upon the line.

At each jerk, the wretched mule expel an agonized grunt—snaps at the men’s shoulders—and probably gives them a sharp pinch, which necessitates immediate retaliation.

The men haul a while, squeezing the poor creature’s diaphragm most terrible. Smaller and more wasp like grows his waist—and last not another inch of line can be got in, and the rope is made fast.

“Bueno,” cries the muleteer, giving the beast a spank on the behind which starts it off—teetering about on the tips of its toes like a ballet dancer. Having done with one animal, the packers proceed to the next, and so on through the lot.

While you are busy with the others, Numbers One and Two have occupied themselves in tracing mystic circles in and out—among and round and round several short, stumpy, thickly branching firs—and, having diabolical ingenuity they have twisted, tied, and tangled their trail-ropes into inextricable confusion. They are standing there patiently in their knots.

Number Three has been entrusted with the brittle and perishable articles because she is regarded as a steady and reliable animal of a serious turn of mind. She has acquired a stomach ache from the unusual constriction of that organ—and is rolling over and over—flourishing all four legs in the air at once.

You may use language strong enough to split a rock—hot enough to fuse a diamond, without effect. You may curse and swear your “level best”—but it does not do a bit of good. Go on they will, till they kick their packs off. And then they must be caught —the scattered articles gathered together—and the whole operation commenced afresh.

Text and ilustration from the Earl of Dunraven, The Great Divide: Travels in the Upper Yellowstone in the Summer of 1874, London: Chatto and Windus, Picadilly, 1876. pages 139-141.

You can read a condensed version of The Earl of Dunraven’s book, The Great Divide, in Adventures in Yellowstone: Early Travelers Tell Their Tales by M. Mark Miller.

If you go…

M. Mark Miller will sign copies of his book, Adventures in Yellowstone, from 10 a.m. – 3 p.m. on Aug. 10-11 at the Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone National Park.