By Ruffin Prevost

MEETEETSE, WYO. — The greater Yellowstone area is cherished for its unspoiled landscapes and abundant wildlife. But it’s hardly a region that most people think of as an archaeological treasure trove. Most people, though, are wrong to think that.

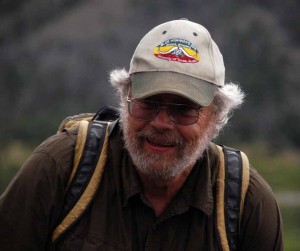

That’s the viewpoint of Larry Todd, an archaeologist who grew up in Meeteetse, near the eastern boundary of Yellowstone National Park and surrounded by the Shoshone National Forest. Todd has worked for more than 30 years studying traces left by ancient peoples in places as diverse as France, Ukraine and Ethiopia, as well as teaching in Colorado and Wyoming.

But for the past decade, he has stayed close to home, studying remote and rugged archaeological sites in northwestern Wyoming, including along the Wood River area near Meeteetse.

“You’re living in one of the great gems of natural and cultural resources you’re going to find anywhere,” Todd told a group in July during a field trip to the Double D Ranch sponsored by the Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

Todd led about two dozen hikers to a high bluff in the Shoshone Forest overlooking the remote site where Amelia Earhart had started building a cabin to escape the public spotlight before she disappeared while flying over the Pacific Ocean in 1937.

The subject of considerable public interest, Earhart’s historic cabin is now being restored. But Todd was more interested in learning about a mysterious hilltop ring of stones and wooden supports first documented in 1969, which he and others have been studying for the last few years.

Ancient outpost

Researchers have speculated that the outpost was used as an ancient fort or hunting blind, but they have had little hard evidence to help date the site or better determine its exact use. At least not until July.

That’s when Todd was discussing the site with his group of GYC visitors and Kaitlyn Simcox, an archaeology student working with Todd, serendipitously found a flake of obsidian and a sheep bone as Todd spoke.

The tiny fragments, each smaller than a nickel, offered what Todd said was “strong evidence of prehistoric use” of the site, possibly for hunting or butchering sheep.

“Before we got here today, this was a totally enigmatic rock structure,” Todd told the group, beaming with the thrill of a discovery that might seem inconsequential at first blush, but that was deeply important to him.

The artifacts found by Simcox are among more than 80,000 cataloged since 2002 by Todd and others working on the Greybull River Sustainable Landscape Ecology project.

Though white settlers have frequented the Yellowstone area for only a couple of centuries, indigenous people have moved through and lived in the region for roughly 13,000 years, Todd said.

Finding traces of their presence, even tiny items like flakes of obsidian shed when making tools or projectile points, isn’t as hard as it might seem, he said.

Sites near water, with lots of wildlife, in scenic areas or with wide-ranging views have always attracted people.”The places that were favored and used in the past are the same places that are used today,” he said.

Todd and others are working to to shine new light on the rich but under-appreciated cultural history of the Shoshone Forest. The Greater Yellowstone Coalition asked its supporters to follow Todd to a few of his Wood River sites so they could share their ideas with others, including administrators finalizing the Shoshone Forest management plan.

Sheepeaters of Wyoming

Cody resident David Dominick said it was important to document and preserve sites like the one he visited in July with Todd.

While a student at Yale University in the 1960s, Dominick studied the Sheepeaters, a reclusive and resourceful band of Indians who lived at high elevations in northwestern Wyoming, including around Yellowstone.

There is still plenty to learn about the Sheepeaters and others who lived here, Dominick said, but forest planners must put a higher priority on cultural resources.

Todd hopes the work of “trying to find the stories of these multiple generations of people who lived here” will help the public better appreciate the hidden human history of the region.

Working with the U.S. Forest Service, universities and other agencies, Todd and other researchers are documenting a multitude of prehistoric and early white settler habitation sites across the Shoshone Forest. Most of the time, researchers photograph and catalog items, but then place them back as they found them, practicing what Todd calls “catch-and-release archaeology.”

“For me, unlike Indiana Jones, the real treasure of archaeological research is well-coded data,” he said.

The reward for Todd also lies in learning more about how people have used local landscapes through millennia, and sharing those stories with present-day inhabitants.

“We are part of a community of people that have been interacting with this landscape for thousands and thousands of years,” he said.

Public comments on the Shoshone Forest management plan revision are due Nov. 26 and may be sent to [email protected].

Contact Ruffin Prevost at 307-213-9818 or [email protected].

The Shoshone Forest managers can’t see the cultural resources for the trees…especially from behind their desks.