By Ruffin Prevost

MAMMOTH HOT SPRINGS, WYO. — Yellowstone National Park managers have decided against establishing new backcountry use restrictions in the Hayden Valley after an extensive review of grizzly bear attacks throughout the park over the last four decades.

A range of potential restrictions on hikers in the Hayden Valley were up for consideration in response to two separate fatal bear attacks there in summer 2011. Park officials will instead focus on improving safety messages for day hikers.

Fatal bear attacks in Yellowstone are exceptionally rare, but they generate intense public interest.

“When we have two of our park guests killed in any way, management takes a closer look to see if we can improve safety for our visiting public,” biologist Kerry Gunther said in October during the Biennial Scientific Conference on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Gunther, who leads Yellowstone’s bear management program, discussed the findings of a study that looked at the circumstances surrounding every grizzly-caused human injury in the park since 1970, the advent of modern bear management in Yellowstone.

The goal of the study was to help Yellowstone Superintendent Dan Wenk and other park managers decide if special restrictions should be placed on visitor use in the Hayden Valley, where 23 percent of the park’s bear-related injuries since 1970 have occurred. The study yielded a wide range of data from dozens of incidents to help guide that decision.

Ultimately, park managers decided against any Hayden Valley restrictions, including options like night closures, mandating the use of bear spray, limiting off-trail travel, seasonal closures or requiring hikers to travel in groups of three or more. Previously established bear-related seasonal closures elsewhere in the park remain in effect, and were not part of the study.

“We will continue to improve our bear safety messages and our delivery of those messages, specifically targeting casual day hikers,” Yellowstone spokesman Al Nash said Tuesday in an email.

A big part of that message is likely to focus on recommending that day hikers carry bear spray, which Gunther said has been “94 percent effective in stopping aggressive behavior in bears when deployed” in incidents across North America.

In 79 percent of the Yellowstone cases Gunther reviewed, hikers were not carrying bear spray. Too many hikers don’t keep their bear spray where they can easily reach and use it, Gunther said. Only 67 percent of those carrying bear spray in Yellowstone were able to successfully use it during bear incidents over the last 42 years.

While overnight campers in Yellowstone are likely to carry bear spray, only 16 percent of day hikers in the park carry it, he said. Park officials have said they would like to increase that number.

Another safety measure is to hike in groups of three or more, he said. Since 1970, 93 percent of grizzly-caused human injuries came when visitors were hiking alone or with only one other person.

Despite the often sensational headlines generated by bear attacks in Yellowstone, a visitor’s chances of being injured by a grizzly are slim, Gunther said, especially for the vast majority of visitors who never venture far from main roads and developed areas.

While the odds are relatively higher if you’re entering the backcountry, the park averages only about one bear attack each year, he said.

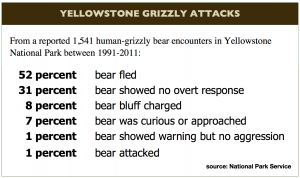

From 1991-2011, there have been 1,541 reported human-grizzly encounters in the Yellowstone backcountry, with less than 1 percent of those incidents resulting in an attack, he said. That makes for a relatively small sample size for the study, but simply because bear attacks are so uncommon.

Gunther’s bear incident study was among a few dozen highlighted at the October conference aimed at demonstrating the event’s theme of “linking science and decision making.”

But with the persuasive power of science unable to convince every visitor to hike in a large group or carry bear spray, the park is turning to another resource for help.

“We’re consulting with Disney” on how the company achieves voluntary safety compliance at theme parks, Gunther said. “They manage many more visitors than we do.”

Contact Ruffin Prevost at 307-213-9818 or [email protected].

I work in Yellowstone during the summer. I’ve seen first hand how people ignore signs and other information pertaining to bear safety. I just don’t see how visitors are now going to suddenly start paying attention to bear safety information, when they haven’t for years.

I think park officials should restrict access to Hayden Valley. While employed in the park for the past two summers and also during numerous vacations, I’ve watched too many visitors seeking photographs get dangerously close to bears in the valley and elsewhere. They are warned by park signs, park info, and park personnel not to do so, but they blatantly fail to heed these warnings.

Yellowstone is a 2 million acre park, and there are numerous other trails for hikers to use. It’s a known fact that many grizzlies inhabit Hayden Valley, so I think park officials are asking for trouble by deciding not to restrict hiking in this area. The reason they don’t want to do this is because the public always whines about such restrictions, but that’s not a good enough excuse–especially when many of these visitors are irresponsible and don’t obey regulations.

The reduction of bear/human conflicts, as well as the safety of both bears and people, should be the main consideration here–not public pressure. Relying on information alone to achieve these goals, rather than restricting visitor access to Hayden Valley, is simply playing with fire.

Only the U S federal government can list a species as endangered, and then train you how not to get killed by it.

To “focus on improving safety messages for day hikers” makes complete sense. We’ll have to wait and see what the improved educational efforts will be. I would also like to see some enforceable public safety regulations short of completely closing any areas.

I don’t favor closures or visitor restrictions to an area, but what’s wrong with demanding that bear spray be carried?

I think a lot of people visiting the park are like me and don’t hike out on the trails because of the fear of running into a bear. I have considered purchasing bear spray so that I would feel safer and perhaps venture out onto some of the trails, but the spray is a bit expensive to purchase and then not use, even as insurance. Perhaps if the park were to “rent” cans of bear spray to visitors who, if they didn’t use it, could return it. Set a nominal rental fee, collect a credit card number as a guarantee of return (or payment if not returned) and then maybe more people would consider carrying the bear spray.