By Ruffin Prevost

A ruling earlier this month by a Montana District Court judge has upheld a plan to allow bison to roam freely in a designated area north of Yellowstone National Park. But predicting when bison will leave the park—and how many will be on the move—is hardly an exact science.

So park researchers are developing a predictive technique using statistical analysis, weather models and historical movement records for tagged bison to get a better idea of what each year’s migration patterns might look like.

When hundreds of bison move through a small town like Gardiner, Mont. at the north entrance to Yellowstone, they have the potential to damage property, injure people and transmit disease to livestock.

Park managers and other wildlife agencies try to reduce those potential conflicts, but don’t always know where and when the animals will move, said Chris Geremia, a National Park Service researcher at the Yellowstone Center for Resources.

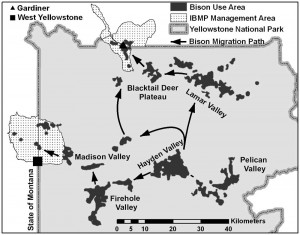

In 2000, wildlife managers developed a bison management plan based on their best idea of how the animals had been moving around the park and its bordering lands, Geremia said in October during the Biennial Scientific Conference on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

“But the bison didn’t move as we thought they might,” Geremia said. Initial movement models were too simple, and far more bison left the park than expected.

Bison numbers grew in unexpected ways, and between 2001-09, approximately 3,700 bison were slaughtered as part of efforts to cull herds and reduce conflicts outside the park.

Researchers started working on a new predictive model, putting tracking collars on more bison to better understand their movements.

Geremia’s research showed that different groups in different places moved around for different reasons.

Bison in the central herd that moved toward the Firehole and Gibbon rivers, for instance, might be more likely to stay near thermal features as snow piled up, rather than moving out through West Yellowstone, Mont.

But animals in the northern herd were more sensitive to the availability of forage when deciding whether to leave the park through Gardiner, he said. So deep snows often drive them out of the park in search of more accessible grass at lower elevations.

Simulations based on the improved model suggest that culling up to half of the bison that migrate out of the park still won’t prevent large recurring migrations in the future. Likewise, keeping overall park bison populations at the low end of acceptable ranges might reduce major migrations, but it won’t eliminate them entirely, the model indicates.

Geremia said his research suggests that if wildlife managers want to avoid future large-scale slaughters like those seen over the past decade, it will be necessary to limit overall numbers and to allow increasing numbers of bison to wander outside of the park during the harshest winter periods.

The predictive model Geremia and other researchers have developed is likely to play an increasingly important role in helping managers know what to expect when Yellowstone bison start to move.

Contact Ruffin Prevost at 307-213-9818 or [email protected].